By: Ryan H. Flax

(Former) Managing Director, Litigation Consulting

A2L Consulting

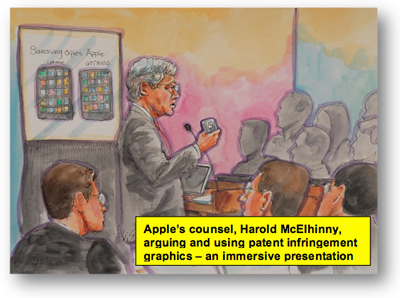

In last week’s article on the conclusion of the Apple v. Samsung patent infringement trial I emphasized that it would be the storytelling and the patent litigation graphics that accompanied the storytelling that would win the case for either Apple or Samsung. Well, now the jury has returned its verdict: 6 of the 7 Apple patents are infringed (willfully) by Samsung (3 utility patents and 3 design patents), none of Apple’s patents are invalid, and none of Samsung’s patents are infringed by Apple. The jurors awarded Apple $1.05 billion, or just less than half of what it asked for.

The amazing, but not unexpected, thing about the jury’s verdict is not the overwhelming victory for Apple, but how the available post-verdict jury interviews completely validate the points made in last week’s article. As expected, the verdict was only superficially based on the law and evidence, but more so on the fact that Apple’s counsel had the better story and better intellectual property graphics (and the juiciest tidbit of evidence around which the story could be woven and graphics designed).

Jurors Want a Story, Not a Legal Case

When asked to point to the evidence that compelled their verdict, one juror – Manuel Ilagan – explained, “on the last day, [Apple] showed the pictures [below] of the phones that Samsung made before the iPhone came out and ones that they made after the iPhone came out,” and this visual evidence at the closing was enough!

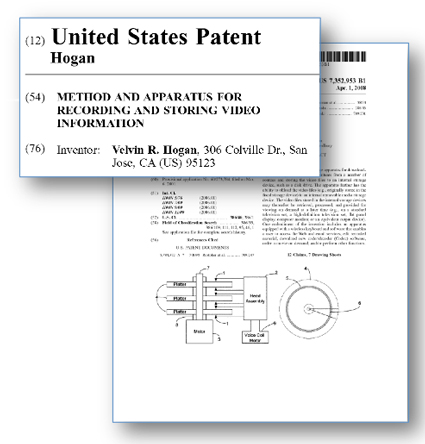

Juror Ilagen went on, “we were debating about the prior art. Hogan was jury foreman. He had experience. He owned patents himself . . . so he took us through his experience. After that it was easier. After we debated that first patent – what was prior art – because we had a hard time believing there was no prior art. In fact we skipped that one, so we could go on faster. It was bogging us down.”

So, the jury skipped talking about the difficult evidence, instead relying on how they felt about the case and on the story weaved by plaintiff’s counsel. And, as discussed below, relying heavily on the background and experience of the jurors.

Speaking of the jury foreman – Velvin Hogan – he also reported in a post-verdict interview that he had a revelation after first night of deliberations while watching television (he called it his “a ha moment”), explaining, “I was thinking about the patents, and thought, 'If this were my patent, could I defend it?' Once I answered that question as 'yes,' it changed how I looked at things.” So, once more, a juror (the foreman no less) reported basically disregarding the complex specifics of the law and evidence, here going with his instincts in deciding the validity of Apple’s patents and then deciding whether they were infringed.

Another juror – Aarti Mathur – expressed to reporters that, “it was a very exciting experience and a unique and novel case.” As a litigator, can you imagine one of your jurors saying this about your next trial – what would you do to provide this kind of exciting experience for them? This was a patent case and yet it instilled this feeling of excitement in the jurors. Research establishes that the best way to do this is by immersing the jurors in argument and litigation graphics throughout the trial. You want to get them interested and keep them interested.

Another juror – Aarti Mathur – expressed to reporters that, “it was a very exciting experience and a unique and novel case.” As a litigator, can you imagine one of your jurors saying this about your next trial – what would you do to provide this kind of exciting experience for them? This was a patent case and yet it instilled this feeling of excitement in the jurors. Research establishes that the best way to do this is by immersing the jurors in argument and litigation graphics throughout the trial. You want to get them interested and keep them interested.

Free E-Book - Click to Download

Guide to Engaging Trial Technicians

Seasoned patent litigator, Sal Tamburo, a partner with Dickstein Shaprio LLP noted, “patent litigators, and really litigators of any complex subject matter, face a difficult task when heading to trial. The law is complicated as is the technology and it is our job to convince jurors, who are usually unfamiliar with the nuances of either the law or the technology, that we’re right and should win. In essence, we need to prepare two cases, one for the jurors that is interesting, compelling, and persuasive, and one for the district and appellate courts that is solidly based in the necessary legal proof.” Sal's right.

It was apparent that the complex law of patent infringement and the overwhelming jury instructions made it all but impossible for the Apple v. Samsung jury to really decide the case on its merits. Not only were the jurors confused by the verdict form, but they actually came back with inconsistent verdicts and damages awards, e.g., awarding damages of $2 million on a patent they found not-infringed, and had to be sent back by the judge to resolve the inconsistencies. This little “speed bump,” however, did not slow them down much.

As I reported in the article last week, this was a case so complicated that the judge begged the parties to settle before it went to a verdict (calling it a “coin toss”) and was also a case in which the jury instructions took two hours to explain and included a 109 page document. With all this complexity and nuance of law, these jurors were nonetheless able to return a verdict in just under 22 hours. This turn-around time would be extraordinary for even a simple case and is beyond imaginable for this patent case.

Jurors Want Great & Useful Graphics

In addition to juror Ilagan’s expressed reliance on Apple’s patent infringement graphics, according to its foreman the jury cut through unnecessary work by hand-drawing a matrix on a notepad to illustrate which patents Apple said were infringed by each of 26 Samsung smartphones and tablet computers. This jury-created graphic is exactly the type of trial graphic counsel should have shown the jury during its closing arguments and then requested be entered into the record as a summary of evidence so the jury could take it with them to the jury room.

Juror Ilagan said, “my impression was that [Apple's attorneys] Bill Lee and McElhinny were pretty good in their presentation and questioning of the witnesses.” Mr. Ilagan was also complementary of Samsung’s counsel’s presentation (recall, this was a “coin toss”).

Juror Ilagan said, “my impression was that [Apple's attorneys] Bill Lee and McElhinny were pretty good in their presentation and questioning of the witnesses.” Mr. Ilagan was also complementary of Samsung’s counsel’s presentation (recall, this was a “coin toss”).

As I mentioned in last week’s article, with effective patent litigation graphics attorneys can teach and argue from their comfort-zone – by lecturing, but the carefully crafted graphics will provide the jurors what they need to really feel they understand what’s being argued and give them a chance to agree. Most people, including judges and jurors, are visual learners and in court litigators must play on this battlefield and with the appropriate weapons.

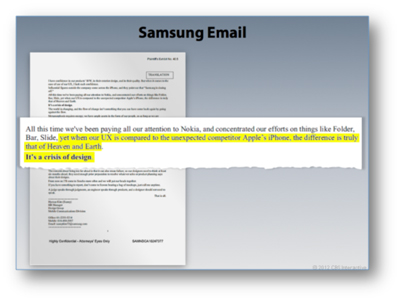

Jurors Will “Hang Their Hat” on Bits of Evidence

Jury foreman Hogan explained that the jury’s decision was based on documents illustrating Samsung’s intent to closely mimic the look of the iPhone and that “certain actors at the highest level at Samsung Electronics Co. gave orders to the sub-entities to actually copy, so the whole thing hinges on whether you think Samsung was actually copying. The thing that did it for us was when we saw the memo from Google telling Samsung to back away from the Apple design. The entity that had to do that actually didn’t back away.” The litigation graphic to the left illustrates this important evidence.

Jury foreman Hogan explained that the jury’s decision was based on documents illustrating Samsung’s intent to closely mimic the look of the iPhone and that “certain actors at the highest level at Samsung Electronics Co. gave orders to the sub-entities to actually copy, so the whole thing hinges on whether you think Samsung was actually copying. The thing that did it for us was when we saw the memo from Google telling Samsung to back away from the Apple design. The entity that had to do that actually didn’t back away.” The litigation graphic to the left illustrates this important evidence.

And, so, on the back of one email chain, the hammer fell on Samsung to the tune of a billion dollars.

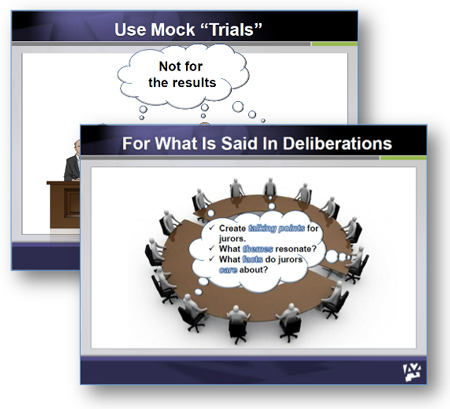

This point is very instructive. It shows us that testing litigation facts, themes, and stories before trial with mock jurors is an important tool in crafting a persuasive and winning case. Before you get to the courtroom, you want to know what facts resonate with mock jurors of the same demographics as your jury pool so you’ll use the right ammunition when it counts.

This point is very instructive. It shows us that testing litigation facts, themes, and stories before trial with mock jurors is an important tool in crafting a persuasive and winning case. Before you get to the courtroom, you want to know what facts resonate with mock jurors of the same demographics as your jury pool so you’ll use the right ammunition when it counts.

You Must Use Jury Consultants

Another interesting take-away from this jury’s verdict is that it relied heavily on the backgrounds and experiences of the jurors, even to the disregard of the law and evidence presented at the trial and instructed by the Court. This is instructive and shows how important jury consulting can be for litigators.

For example, the jury’s foreman (Mr. Hogan) was an engineer and holds a patent (relating to video compression software, at right). The jury relied heavily on him to deal with the patent law issues in the jury room and he even told the Court that the jurors had reached a decision without needing the instructions!

For example, the jury’s foreman (Mr. Hogan) was an engineer and holds a patent (relating to video compression software, at right). The jury relied heavily on him to deal with the patent law issues in the jury room and he even told the Court that the jurors had reached a decision without needing the instructions!

Experts agree this isn’t uncommon at all. According to Stanford Law School Professor Mark Lemley, “if there is one juror who seems more clearly knowledgeable than the others, the jury will often look to that person to help them work through the issues, and perhaps elect him foreman.”

Hogan, told the court he had served on three juries in civil cases, spent seven years working with lawyers to obtain his own patent covering “video compression software,” and worked in the computer hard-drive industry for 35 years. Based on this he was elected jury foreman and, I suppose this background also relieved the other jurors of having to worry too much about the gritty nuances of the law of patent infringement and validity because Mr. Hogan could sort out those details for them.

It’s been reported that Mr. Hogan said that the jurors were able to complete their deliberations in just three days and much faster than almost anyone predicted because a few jurors had engineering and legal experience, which helped with the complex issues at play. According to Mr. Hogan, once they determined Apple's patents were valid, jurors evaluated every single device separately.

These leaps in deliberations are remarkable, but, as discussed in last week’s article, predictable.

One More Thing

Foreman Hogan explained in a televised interview his thought process regarding the law of patent validity and how he helped the rest of the jury come to terms with the law – it’s clear that (although he’s obviously very intelligent) he does not really understand it and he and the rest of the jury went on their gut instincts in most instances. To a patent litigator, like myself, his interview is frightening on one level because it shows how hard it is to get through to lay jurors and even technically experienced jurors on the nuances of patent law and how it should apply to the facts.

But, it’s also very instructive. All litigators should watch and note his explanation of the jury’s process. I think Mr. Hogan is fairly representative of what the top of the juror food chain is like and he’s a good place to start when developing your trial strategy. Cater to their needs in proving your case – use graphics extensively, use jury consultants, and test your case.

Oh, there is one more thing. Just for the sake of stirring the pot, here’s an ironic and amusing video of Steve Jobs discussing what great artists (and presumably great innovators and great companies, including Apple Inc.) do to succeed (can you guess what it is?):

I wish good luck to both the parties and their counsel in the appeal process, which I and other patent experts will be attentively watching. (write this down: it’s my bet that this case ultimately settles before any opinion from the Federal Circuit). Stay tuned.

Ryan Flax is the Managing Director of Litigation Consulting at A2L Consulting. He joined A2L after practicing as a patent litigator who contributed to more than $1 billion in successful outcomes.

Other patent litigation graphics related resources on A2L Consulting's site:

Leave a Comment